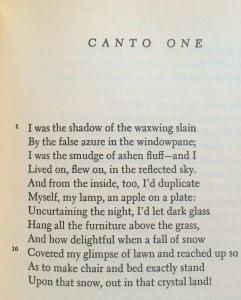

Pale Fire: Four Cantos (1962) by John Shade, is a book that stuck in my mind and will not dislodge. It first appears to be a commentary on a 999-line poem in rhymed couplets for dedicated students of literature. The commentary that follows is apparently written by a literary critic, George Kinbote. If you have ever tried to read an academic text book, with their footnotes, glossaries, appendices, and put it straight back down with a yawn – as reading them has little continuous flow – pay close attention here. It is true some of them are as dry as cat’s dirt; the dryness is alleged to equate to intellectual rigour, as juiciness is to hyberbolic fiction; yet this one smells different, as it provokes questions of its authorship, stirring up a riddle of ego, alter ego and splintered selves. So it still has a lot to tell us about the psychopathology of our age. On reading Nabokov, I also often suspected that he was a modern magus in the literary arts. Scratch the surface even a little, and you discover oblique references to the tarot, astrology, parapsychology, the qabalah and astrology, and ‘fatidic moments,’ so it is time to shine the focus into these areas, as his birthday on 22nd April passes.

This dry-looking tome begins with a foreword in mock-serious tone analysing the text, detailing dates, and offering revisions of and contemplations of the meaning of the poem. Thereafter, a quirky personality (or multiple personalities) seeps through like chinks of light through an iron grille revealing a crooked universe. This is the man from Zembla, the annotator, George Kinbote, whose attempts to explain the poem and poet result in taking over Shade’s life. He is vegetarian to Shade’s carnivore, and it is more than clumsily hinted that Kinbote is fond of boys, not girls. Yet, they share the same birthday. The reference to the shadow in Jung’s terms is not accidental: it soon becomes clear that the commentary is the reassembled novel itself, and packs a puzzle which is still being unpacked today about who authored which section that contains the ‘other’ author. Pale Fire can lead us along the very wild goose chase that Nabokov wanted: on the surface it is impenetrable, and both the poet and the critic are eccentric curiosities. But very little is written without careful forethought in Nabokov’s world; fated events are painted with both mannerist precision and heightened exaggeration. Pale Fire emerges as an intricate ruse; a story within a story within a story; it demands that readers understand it on its own terms.

2: Nature, Artifice, Self and Shadow

If all the above sounds off putting, we might ask why should we bother reading it? Surely not for Shade’s poem Four Cantos? T.S.Eliot’s Four Quartets it most definitely is not. So is it for the artful commentary which comprises the novel? We bother for exactly the same reason that mountaineers say they must climb Everest. It presents a challenge – how to read it without falling off its hidden surfaces. Shade’s mad neighbour/stalker George Kinbote usurps his world by ‘annotating’ it half to death, and littering it with red herrings. But blink and the novel is not there, posing as academic text – all so wickedly Nabokovian. This smoke and mirrors effect led to it being dubbed ‘postmodern.’ Nabokov believed, much like in the Vedas, with the word Maya, that nature was a deceiver, an illusion in which we believe all too easily. Therefore art, or specifically fiction, is by definition a double deception. To have a double authorship debate at the core of the book is triple deception. I also feel there is a strong whiff of the esoteric in Nabokov: is King Queen Knave (1968), not a reference to the Tarot?… that life and death are decided by inexorable, but exquisitely ironic, laws of sequence and interconnectedness. Characters, names, colours and numbers and names interlink both within and across novels more closely than in the Qabalah.

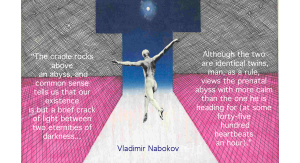

His synaesthesia allowed him to mint startling imagery like new coinage. The opening lines from Speak, Memory (2000) could have been taken from an obscure Tibetan treatise on the bardo states, or a lecture by Allan Watts, but this is given the Nabokov twist, with its ultra-omniscient viewpoint:“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour).” Memories to Nabokov became stronger and stranger the more you love them. But to have this kind of memory, he must have had recall of awareness from outside his physical incarnation, perhaps an OBE (out of the body experience)?

The term ‘pale fire’ is possibly (Kinbote raises doubts) from Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens, referring to the paler light of sun as reflected by the moon, suggesting eclipses. While not a direct reference to astrology, it sets the scene for seeing Nabokov through that lens. The ‘pale fire’ image is also used to describe the flame from the incinerator in John Shade’s back garden, similar to the one from which the original manuscript of Lolita (1958) was rescued by his wife, Vera just before submitting it for publication. Apparently, he had had cold feet about its risque topic.

Pale Fire is a satire on the world of academia, the stalking nature of so called ‘critics,’ obsessives, and the flourishing of rampant, even malignant, egotism which can run rife among writers. Yet, Nabokov relied on critics such as Mary McCarthy to rescue the understanding of his work. Pale Fire differs from any other novel I know not just by have at least two unreliable narrators, and bridging the fiction to non-fiction genre, but also by its use of the curious device of formal notes to construct the story. While this obliges the irked reader to flick pages back and forth to build the picture of Shade’s and Kinbote’s life, the pleasure is in the discovery that its presentation breaks the mould. Startlingly clever, inventive, but also devious and annoying, Pale Fire is a rare cultural artefact; if it does not have a real heart, it has a well functioning artificial one surgically implanted.

Nabokov was intensely private about his real emotions. It is all on the page, where we can admire the sly skill of the invented personas that has critics today arguing whether Shade or Kinbote are two sides of the same personality, and Shade is meant to be seen as the real author of the commentary. Was that planned? We may never know, but it is odd how Kinbote, becoming absurd shifts the sympathy back to Shade, and enhances the importance of the poem which has now been published separately, becoming an orphan. It is as though Nabokov is elaborating his very own internal ‘parts’ therapy on the page but neatly side-stepping the final healing integration.

3: Nabokov’s Asteroid Muses, and Hebe, the Goddess of Youth

While there is much to admire about Nabokov, there are some troubling aspects to his character. But as with most things Nabokovian, nothing is at first what it seems, so I’m attempting to be kaleidoscopic in approach as befits this multi-faceted author; first by peering into his natal chart, and then unraveling the story of his enigmatic brother Sergei.

Lolita (1958) is ultimately a moral book according to Martin Amis. Yet, it was banned and was considered literary porn by many, often those who view sex as ‘dirty.’ Its reputation for salaciousness only increased its notoriety. However, it is not salacious or sensational, but full of pathos and intricate realism. Nabokov’s assured style allows us to savour every nuanced thought and action towards Humbert Humbert’s inevitable final admission that perhaps he had robbed Dolores of her childhood. Though he only shot Quilty, he could be held responsible for Charlotte Haze’s death – another ‘fatidic moment’. The insight is only momentary. What’s striking about the writing style is its highly detailed literary tone mixed with blistering farcical comedy. It has become one of the greatest books of the 20th century; its tone is hard to replicate exactly because of this fine blend of tragic and comic elements, filtered through the mind of a sophisticated, but troubling protagonist. There are moments of lyricism which turn rapidly into scenes of the grotesque, provoking mirth, awe and condemnation all in the same moment.The two films of Lolita (1962) and (1997) only sometimes manage to hint at what lurks on the pages of the book.

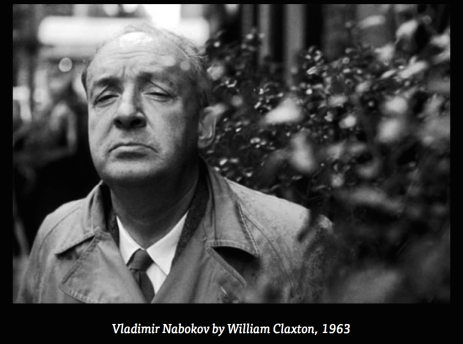

That writers are as subject to their star sign may seem reductive to some, but the evidence is impressive. A casual investigation into his natal chart shows that Nabokov (born 22 April, 1899) was a Taurus, with an Aries Ascendant. The 22nd of April is same day incidentally as Shakespeare – a parallel that probably amused Nabobok greatly. A Writers Astrology states “Look closely at the common biographies of Taurus writers and you will find a close circle of artistic support–with the Tauran’s Olympian capacities for love holding steady at the nucleus…Although Tauruan writers are somewhat rarer to come across than other signs, when one encounters a Taurus writer expect high quality writing coupled with a sensible, rigorous plan for publication.” Nearly all of Nabokov’s work centres around love and he had the devoted love and skilful secretarial and translation support of Vera throughout his life.

While his Sun is in an Earth sign, Nabokov’s chart is dominated by fire, with very little air. Clearly, he was distinguished by a forthright and robust character fully, able to communicate and defend his views. The finer details of his chart are dealt with elsewhere, so a little investigation of where the Muse asteroids are positioned proves fascinating. It comes as no surprise to find that Thalia, the muse of comedy, is almost conjunct his Ascendent in Aries which happens to be four degrees from his Mercury retrograde. This Mercury Retrograde positioning is well known to be good for writers, especially Nabokov who spent a life revising and rewriting his novels, perhaps lending that mischievous edge that characterises Nabokov’s work. Having this placement of Thalia almost guarantees Nabokov’s talent to amuse, an immense charm that is able to be artfully expressed. But to add that touch of mockery and mordant wit, he has Erato the muse of Poetry and Mimicry, also prominent in his Ascendent Aries just a few degrees away.

Technically speaking, Humbert Humbert is not a paedophile, but a hebephile, a fine distinction that eludes most people. Hebe, is the goddess of youth at that point in adolescence which ‘blooms’ before the onset of adult conditioning. The asteroid Hebe is found at 26 degrees of Virgo, which is squared by Saturn at 23 degrees of Sagittarius, which suggests a relationship of young virgin to an older man. Miller notes that Lolita was published just days before the birth of Michael Jackson who has many parallel aspects of Hebe which is semi-sextile his Pluto. In Nabokov’s chart “Pluto and Eros conjoin exactly at 14 Gemini, an image of obsessive/compulsive (Pluto) erotic attachment (Eros), and are tightly squared by centaur Nessus (inappropriate display of sexuality or affection) at 12 Pisces.” While we do not necessarily need to know asteroid positions to understand the character of Nabokov, it nevertheless is fascinating that these alignments exist.

4: Nabokov’s real shadow- his brother Sergei

Nabokov loved masks, twins, and doubles. They recur throughout his work, as they did in his life. Recently, it has been suggested that his brother Sergei was his hidden double. This refraction of selves is part of what makes his work crackle. Nabokov, at least the persona he presented to the world, was very much like character drawn by himself in his own work. He loved to identify rare butterflies and his collection of butterflies is considered as scientific as any in the cannon of lepidopterists, yet he himself would run rings around anyone who attempted to pin him down with any labels. He loved literature but was scathing of other writers, considering himself one of the greatest. He lived his last years in a hotel suite in Montreux, Switzerland, and the barman there said he was a kindly man, but who in all the years he was there never tipped a penny. The barman also suspected he let his wife Vera do all the writing and Vladimir was mostly out catching butterflies.

Of greater concern is that Nabokov is on record as stating he hated homosexuals, yet the writer he adored above all others was Proust who was homosexual. Nabokov has homosexual characters in 17 of his novels, often signalled by the code word ‘mincing’ or that they always have to be women hating. Yet, he rarely spoke of his brother Sergei who loved music, languages and poetry, but who happened to be homosexual. The parallels however between the characters in Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (1941) align to details of Sergei’s life. Yet, Sergei was considered the “shadow in the background” in the family, and particularly of his older brother Vladimir. Grossman argues that admirers of Nabokov should even regret the fact that in spite of much evidence of his humanity, Vladimir was homophobic. Grossman even goes so far as to suggest that the idea for Lolita originated in the experience of Vladimir being fondled in the lap of his wealthy ‘gay’ uncle Ruka when he was eight or nine. Nabokov himself despised this kind of retrospective psychoanalysis, yet it may be worth asking the question how did he really feel about his brother? not to police him after his death, but just to shed light on a common mechanism of shame around diverse sexualities. That Vladimir had a conflicted and contradictory attitude towards Sergei is evident. On the one hand, he had an affection for his younger brother; but on the other hand, he never publicly acknowledged that Sergei was gay, finding it difficult to talk about him without disdain or embarrassment, rejecting his sexual ‘condition’ attributing it wholly to a genetic disorder. This suggests he wanted eventually to come to terms with his complex feelings.Deep down he may have felt too close to Sergei to effectively reveal those feelings, something the family has denied.

While the two brothers’ lives had strange parallels, their fates were utterly different. Vladimir flirted shamelessly with his students in the USA, was feted as a literary demi-god, and died a celebrated author. While Sergei stuttered for years, he found his voice finally in Berlin during WWII and spoke out against the injustices of the Third Reich when he was arrested for making subversive statements, and helping an English ‘friend’ from Cambridge. He was incarcerated in the Neuengamme concentration camp where Sergei helped as many of his fellow prisoners as he could. He died of dysentery and exhaustion there. Vladimir died in 1977, never having written the ‘Real’ life of Sergei as life is the first great deceiver and even his artifice could not have made up these incidents.

Even though Nabokov comes across as a haughty writer in relation to his readers – he openly detested jazz, Plato, manifestoes, clubs, and psychotherapy! According to Amis, Nabokov has an amorous style, and he approaches the reader as “the dream host, giving us his best food, and best wine” whereas James Joyce is in the bare parlour saying gruffly help yourself to a plate of conger eels somewhere in the kitchen. To Nabakov, a novel is a ‘fairytale,’ not a bit of sociological history. So we still have these fairytale-ish entertainments at each novel which is a Nabokov house party.

It is useless to summarise the complexity of Nabokov in a few paragraphs, but these notes allow me think that Sergei was perhaps the living embodiment of that pale fire to Vladimir’s tremendous flame-like sun. Sergei could have been the ‘arrant thief’ in Vladimir’s life. Vladimir blazed while Sergei reflected and revolved around his older brother, living unknown almost in his shadow, as his shadow self, or one of them. Vladimir, having Thalia in his ascendent suggests he was well connected to his muses, and fully assertive of his creative talents as the farcical shenanigans of Pale Fire demonstrates. And who could forget Lol- Lolita? He produced works of lasting value, with tragicomic overtones, premised on that underlying bleak but quasi esoteric magician’s view of life. As his birthday passes, we might revisit this apparently deadly dry book, by no means pale, in order to rediscover its inner juiciness, riddled not with ‘stillicide’ but with that spark of invention that still has the fizz and kick of a lethal cocktail served up with relish.

© Kieron Devlin,

April 2015

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kieron Devlin arthealswounds.wordpress.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content in accordance with a Creative Commons License. Should any duplication of images have occurred in this site, from sources not mentioned, please message the author so that the image can be credited accordingly. Many thanks. Kieron Devlin

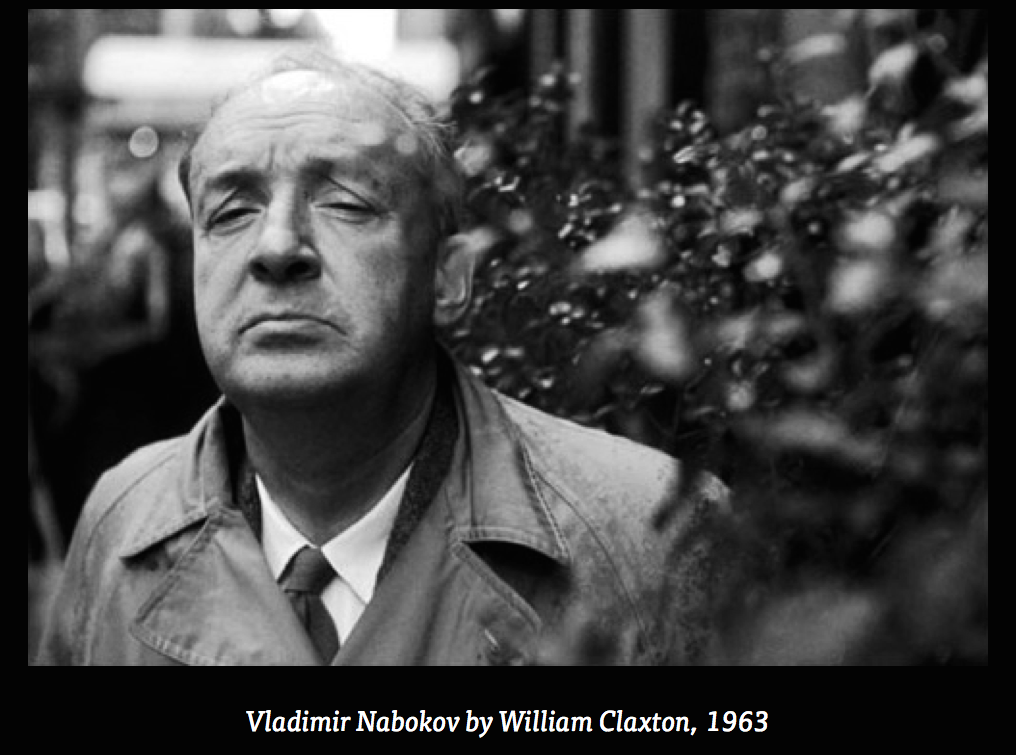

I’m afraid that famous picture you’ve posted of a sensitive, swan-necked aesthete, soon to be robbed of the rest of nearly everything but his talent, butterflies, his future wife and his life, is not fey Sergei but butch Vlad. Unless it can be finally revealed the two were twins…?

LikeLike

Thank you for identifying that, I will try to verfiy and remove if it is not Sergei.

Best wishes

K

LikeLiked by 1 person

“But very little is written without careful forethought in Nabokov’s world”

that is so very true.

“critics today arguing whether Shade or Kinbote are two sides of the same personality, and Shade is meant to be seen as the real author of the commentary”

In a way, that is true (read below), but they were likely intended to be seen two separate entities.

https://palefireexplained.blogspot.com/2019/06/pale-fire.html

.

LikeLike